"HE SAT IN THE KITCHEN WITH A GLUE DISPENSER AND SCISSORS, QUIETLY ORGANIZING HIS CULINARY LOVE LETTERS"

FROM FEBRUARY/MARCH 2023 ISSUE OF WEST END PHOENIX

My mom learned to cook Jewish to win over her in-laws. In the decades that followed, my dad, a newspaper man, spent decades clipping recipes and assembling them in big black binders for her - the best way he knew to show his thanks

First, a food fight

My parents’ first fight was over frozen lamb. The year was 1965, and my newlywed mother, Toshiko, 26, wanted to cook with my father, Sid, 29, who – despite being completely inept in the kitchen – talked a huge game about his lamb roast.

Though he was a promising journalist with a successful career ahead of him, my father was a terrible communicator who got uncomfortable when put on the spot. Toshiko, from Tokyo, had never even cooked rice, and knew nothing about the luxury of frozen goods and how to prepare them. Poor Sid refused to explain the finer points of defrosting, so my mother got upset and cried, wondering if a fiery two-week courtship with a nebbish Jewish guy that resulted in marriage and a move thousands of miles from her family had been the best decision of her young life.

As far as my father’s approach – or non-approach – to emotional communication is concerned, over the years I’ve had to face facts: The apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree. But neither has a great recipe for Apple Fritters, Grassmere Apple Spice Jam, Baked Apples Pavillion or anything apple-related. This is because what Sid lacked in simple communication skills, he made up for by clipping recipes. Lots of them.

Every family has its sacred objects, treasures that hold zero financial value. For me, it’s a series of my father’s self-assembled cookbooks – seven nondescript black binders – that, as I’ve always seen it, contain the secret to my parent’s deep, and at one time almost forbidden, love.

The food files

Each of the black binders is organized into categories separated by colourful retro page dividers that feature simple headings like poultry, fish, soup, vegetables, breakfast and baking. Clipped from issues of The New York Times Magazine, the recipes were amassed over decades and have been yellowed by time, crispy to the touch, my father’s handwritten notes filling the empty spaces.

As artifacts, these binders speak to a different time, when casseroles were king – governed by a Western palate and spiced up with a fawning interest in the East. Having a grand dinner party? Get sophisticated by serving Fried Artichokes Azzuro, Kuei Yüen T’ang (Dragon-Eyes Sweet Soup), Masala Vangi or Truite Véronique finished off with Hanksdabadar (Turkish Delight).

My family traditions are wrapped in these pages. Take for instance a Chestnut Almond Torte so delicious it became the official dessert of our annual Japanese New Year’s Day meal, where mouth-watering dishes hold symbolic value for the year ahead. The Chocolate Sabayon Pie, meanwhile, created so much commotion around the dinner table that it felt like a group panic attack until it was in our mouths.

The binders overflow with Western standards like meatloaf, beef stew and poached salmon. There are instructions on how to make the perfect hamburger, clean squid and bake with puff pastry, plus way too many variations on mayonnaise. There are oddities, like Gefilte Fish Beggar’s Purse; stately ones like Cambodian Hot-Pot Banquet With Vegetables and Seafood; meta dishes like Chicken Stuffed With Scrambled Eggs. My mind reels from the memories of sitting in my family kitchen around a pine table, covered in blue gingham and set by my brother and me, all the dishes prepared entirely by my mother. My father giddy with anticipation. My stomach doing somersaults.

Food as bridge building

Sid’s parents had been shocked that their eldest son had secretly married a goy, let alone a rose from Tokyo. This was the ’60s and the Japanese were still the Japs. So Toshiko learned how to make kugel, the Jewish noodle casserole (giving them grandchildren helped as well). Then, with the help of a cookbook from her mother-in-law, Clarice Adilman, she started to pump out blintzes and cow tongue – becoming less of a Suzuki and more of an Adilman. Over time, bags of her mandelbroit, a Jewish biscotti, would be secretly delivered to Jewish friends around town. Secret because if their mothers caught wind that some hussy named Toshiko made better mandelbroit than they did, all hell would break loose.

Food as therapy

It’s a wonder how my mother kept the plates of her life spinning at such an intense speed in those early years. On top of bringing up two children, she changed careers to become a sought-after Japanese/English translator, regularly flying all over the world to help people communicate, all the while making sure great food was always close at hand for us.

Toshiko’s approach to cooking was, and still is, similar to the way she approaches life: practical and no-nonsense. She used her postwar Tokyo thrift to haggle with the gregarious fish mongers, spice dealers and vegetable barons of Kensington Market. And eating in Japan had opened her up to diverse cuisine: Tonkatsu is basically wiener schnitzel, noodles are noodles everywhere – and she wasn’t afraid of the White Man’s disease: cheese.

My mother would never say that she expresses herself through her cooking, just as she never identifies as an artist, though she is one across many mediums. But the effect of her food did the work of great art: It helped others to see the world and her differently.

To my father’s glee, Toshiko learned to recreate restaurant meals in her kitchen. He dined on cloud nine while his scissors worked overtime, and the food binders ballooned. Our family kitchen hummed with activity and at the centre of it all, the binders reigned supreme. Or so I thought.

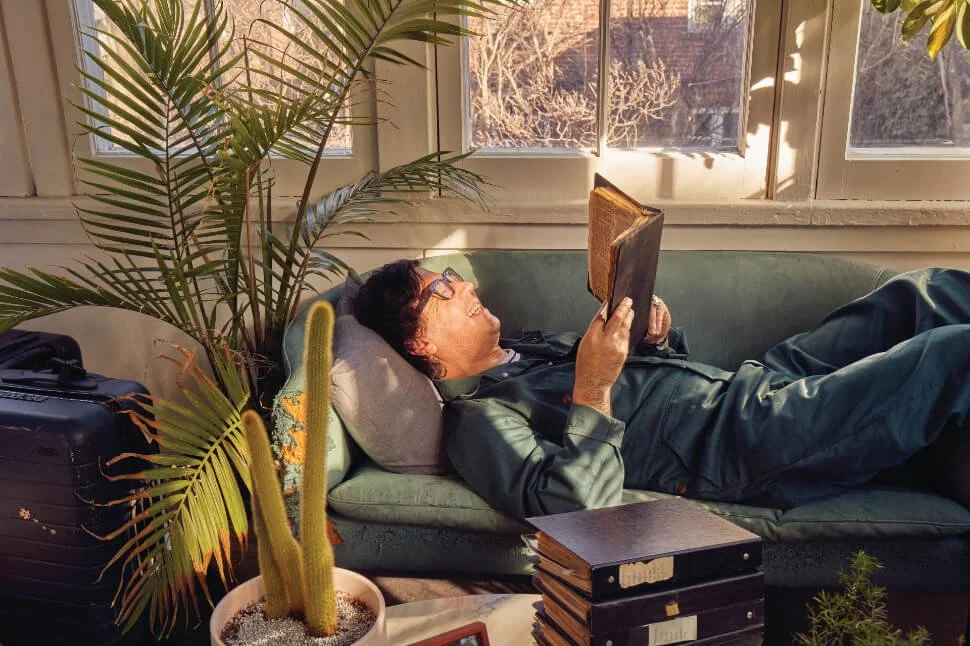

Researching this story, Adilman (above) discovered the binders meant more to himself and his father than they did to his mother. "What do you want me to say?" she replied to him when he asked. "I barely looked at them."

Food bomb

When I recently sat down with my mother to chat about the binders, she was stoic. To every question I lobbed – “When do you remember dad first putting these binders together?” “What was the first dish you made?” “How much did you talk about them?” – her responses were a series of exasperated remarks: “I don’t know.” “How am I supposed to remember?” Mockingly “I have no idea.” And the kicker: “What do you want me to say? I barely looked at them.”

My mother confessed that she maybe made two per cent of the recipes and that they held zero emotional value for her. I remember this so differently. Did I dream of eating these dishes? I asked her what she felt when she looked at my dad’s handwriting on the pages, and she said “Nothing.” She quickly added that a handwritten love letter she found in a sock drawer two weeks after he died meant a lot more. When I asked, “What would you say if I threw them out tomorrow?” she replied, “Good.”

Days later, I realized my framing around the binders was being forced to change. As much as they did contain recipes that tied my family together, their story was becoming more about me and my father.

What to do with Sid

When I was a kid, Sid – then a minted entertainment journalist for the Toronto Star – made a yearly pilgrimage to the Cannes Film Festival to watch films and interview famous people on yachts like Pete Townshend and Cheech and Chong.

On his return, we’d talk in hushed tones as he unpacked sacred rounds of raw-milk Boursault he’d sneaked through customs. But while he was away, I missed him a lot. My wiser older brother Mio taught me to read his articles to catch little messages just for us – the quality of the beaches, the feeling in the air around him. It felt like a game and it brought me closer to him, but it was also too codified for a simple kid like me. I always felt my father’s love, but he was a hard guy to get to know.

Now, sifting through the binders, I’m able to play the game more comfortably. I feel his curiosity, his sense of adventure, his staggering appetite and his overwhelming love for my mother. Though I could have done without the cheese souffle.

As Toshiko sliced and diced, sautéed, sweated and served up delicacy after delicacy – whether the dishes originated from the binders or not – he sat in the kitchen with her, armed with a glue dispenser and scissors, quietly organizing his culinary love letters using the trusted source of The New York Times as his Cyrano De Bergerac – the selector to her deejay. This is a huge stretch that my mother will likely brush away but maybe it was his way of apologizing for that first fight about frozen lamb.

What I know for certain is that food is a love language for my family. I wound up making a television show called Food Jammers that was aired all over the world. My brother and I repaired some brotherly conflict decades ago by making a mockumentary about pies, and we’re plotting a cookbook that could be placed in the cooking, humour or anger management section of the bookstore. To celebrate my mother’s 65th birthday years ago, my brother performed a poem that was essentially all the dishes she had ever made that he loved. It brought the house down.

The seven binders now sit on a shelf in my kitchen. The presence of my father – gone now more than 17 years – is unmistakable. The recipes are an amazing resource and they may even make me a better cook, but most importantly they remind me that my father was always doing his best to communicate his undying love for my mother. He just needed the recipes to help do it.