TORONTO THE JUST

FROM DECEMBER 2020 ISSUE OF WEST END PHOENIX

Our city – like all cities – was built on racial injustice. Here are seven Torontonians on how we can begin to undo that harm

This year exposed the deep and painful ways racism is embedded in every aspect of our society. Now is the time to rethink the systems that have historically oppressed our most marginalized residents and commit to rebuilding a racially equitable Toronto. We asked the city’s brightest thinkers, community organizers and advocates what we can do in the next two decades to make Toronto better for everyone. Their ideas ranged from forming community-owned land trusts for 100 per cent affordable housing and mobilizing the suburban voice for better public transit to turning golf courses into community gardens. These are bold and far-reaching suggestions, but the common theme is empowering the communities that have long been advocating for racial justice.

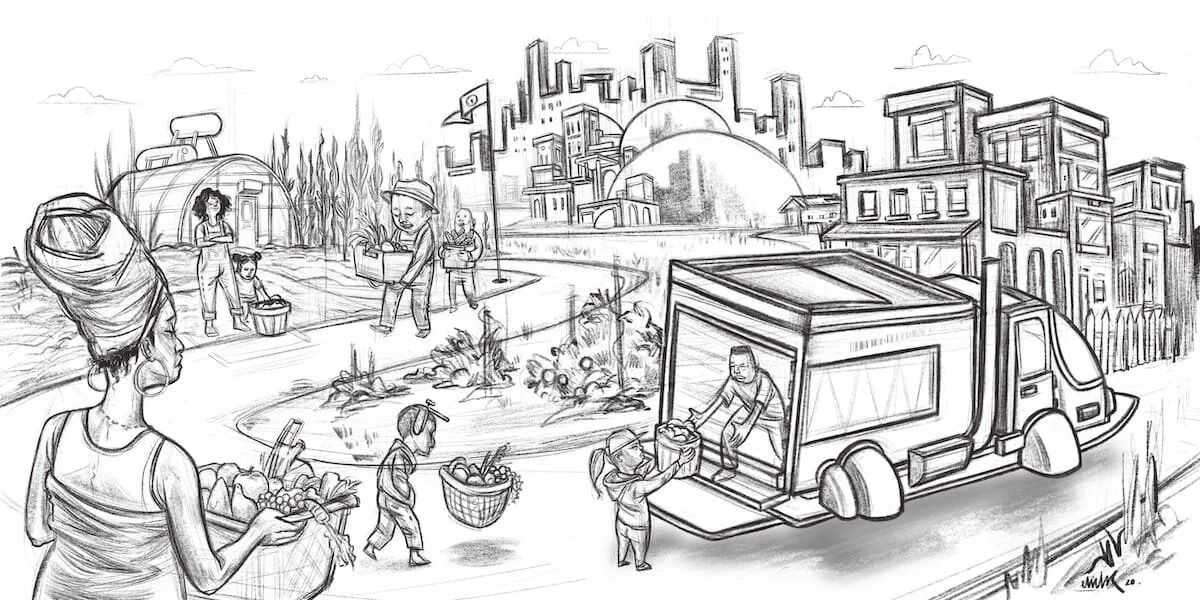

“The phrase that sums up the current relationship in Toronto between race and food is ‘food apartheid,’ a term coined by American activist Karen Washington. Your race and where you live within Toronto have a huge impact on the type of food you have access to and your health outcomes. Why is it that the Jane and Finch community pays more for fresh produce in comparison to other neighbourhoods? It’s no secret that people in our community face high rates of diabetes, high blood pressure and cholesterol.

We need to stop looking at food as a commodity, where big corporations drive a lot of our food policies, and instead as a human right. At a localized level, we need to make public lands, like city-owned hydro corridors and golf courses, available for people to grow food to feed their families and to sell so they can earn a bit of money.

The city needs to develop an actual policy and plan for urban agriculture programs based on Indigenous knowledge and the work community groups have been doing on the ground for awhile. Toronto does not have an emergency food plan. And I don’t mean Band-Aid solutions like food banks. Our food system is very reliant on an outside system to feed us, but to address food security we have to build our own resiliencies. When the pandemic hit, a lot of people got into gardening. On a practical level, we understand the need for food sovereignty, but on a policy level, it doesn’t register. Instead of giving land to developers to continue to build condos that no one lives in, how about we actually look at the practical things, like who is going to feed this large city?”

— LETICIA AMA DEAWUO, DIRECTOR OF BLACK CREEK COMMUNITY FARM

“I live in Malvern in Scarborough, which the city has called an ‘emerging neighbourhood’ – although it feels like a misnomer considering we’ve been underserved with public infrastructure investments for over 30 years. Like the majority of Scarborough residents, the TTC is my primary mode of transportation. The buses are overcrowded, caught in traffic and unreliable, forcing people to consider alternative options like Uber and taxis, or even walking for three kilometres in the winter. Getting around in Scarborough takes longer than going downtown. The two-hour transfer is a clear example of how inequity affects racialized communities who live in the suburbs. Because of the geographic landscape of Scarborough, it takes a long time to get from the grocery store to a doctor’s appointment to the playground.

In the next 20 years, we need to build a Rapid Transit Network to address the overcrowding on buses and to reliably move our populations throughout Scarborough at a much faster speed. We need a system without transit policing, where people can ride hassle-free. The money being used to pay enforcement officers should be redirected to serve the needs of the people, not stigmatize them. In the suburbs, transfers should last the day, or at the very least be extended to four hours. In order to achieve affordable and accessible transit, we need more funding. But we also need to make decisions that reflect the reality on the ground. Oftentimes the needs of the majority are ignored at a heavy cost. Vested interest groups like property owners and developers lobby politicians. These groups of people don’t take transit, but they’re shaping our transit policies. With TTCriders, I am organizing the Transit Organizer School, a leadership program where we’re training residents from the inner suburbs to be local organizers so we can help fill this gap in the decision-making process. People living in the suburbs need to be heard.”

— KETHEESAKUMARAN NAVARATNAM, ORGANIZER WITH THE GRASSROOTS ADVOCACY GROUP TTCRIDERS

“What would a community-controlled vision of a neighbourhood look like? I think about that a lot. Our dream for Chinatown and other Toronto neighbourhoods is for there to be equitable access to childcare, transit, food security, and affordable, social and co-op housing. It would support people on the margins, like sex workers and undocumented folks. That’s what an inclusive community would feel like for us.

One of the biggest issues Friends of Chinatown Toronto is working on is opposing the development proposal at 315–325 Spadina Ave. for a 13-storey building where a one-bedroom would cost approximately $2,500 per month. This is about more than just one particular building. It’s symbolic of the changing character of our community and our city. The current building is home to the decades-old dim sum restaurant Rol San that in many ways is like a community space for families. We’re not opposed to change. We’re opposed to change that worsens our existing community fabric. We know it’s not sustainable to just oppose developments. That’s why we want a Chinatown Land Trust for 100 per cent affordable housing that’s community-controlled and -owned. Solutions from city hall aren’t happening fast enough.

Coalition building is also so important. FOCT has had a lot of conversations with Jane Finch Action Against Poverty, the Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust, Black Urbanism TO and Friends of Kensington Market. We’re building on what’s been given to us from previous generations, including the people who fought against the first displacement of Chinatown in downtown Toronto. As a community group, we made it a priority that our core team be racialized folks, recognizing that civic engagement spaces can be pretty white and more middle- and upper-class. We need to not only support racial justice, but also embody racial justice.”

— DIANA YOON, COMMUNITY ORGANIZER WITH FRIENDS OF CHINATOWN TORONTO

“As soon as the pandemic hit, there were millions of people who immediately had no protections of any kind. In the riding where I ran, Toronto Centre, the monthly $2,000 Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) was more money than many members of racialized, new Canadian communities were making prior to the pandemic. That is not a good state of affairs. But it gives you an indication of what potential a Guaranteed Livable Income (GLI) could have to create a more economically equitable society.

We call it a Guaranteed Livable Income, rather than a Universal Basic Income, because the idea is to make sure people can truly live on it, as opposed to a subsistence living. The intention is to make sure it’s enough of an income so you can breathe and plan, retrain yourself or pursue further education, take care of loved ones or access better housing. We also know that universal programs are ultimately cheaper; the savings in administrative fees [such as rent, utilities, insurance and payroll] could pay for the GLI.

GLI particularly addresses the kind of precarious work, like in the gig economy or low-paying essential jobs, that racialized and low-income people tend to have and that isn’t covered by Employment Insurance or other forms of social assistance. In Toronto there’s a tremendous concentration of wealth and a tremendous concentration of low-income people. There is a significant extent to which poverty is racialized in Toronto. GLI could help narrow the inequality gap, which is a powerful thing for reinforcing democracy and social cohesion.”

— ANNAMIE PAUL, LEADER OF THE GREEN PARTY OF CANADA

“The federal, provincial and municipal governments need to centre the voices and experiences of Black and racialized people most directly impacted by gun violence and allow them to direct the responses. Within these communities, a lot of people will say there’s a role for police. However, there’s also a dramatic overreach because we can access police more quickly than mental health-care or childcare services. An officer will arrive more quickly than the scheduled bus route.

Overwhelmingly, the people that have led the responses have not been the folks directly impacted by community violence. The ideas of the community get screened out by the outsiders leading consultations. Or their ideas are only validated if they can point to an example of where it worked in another jurisdiction. I’m not suggesting we should jettison good public policy or research-driven intervention, but we need more made-in-Toronto resolutions. We also know that people who are more likely to engage in community violence are more likely to listen to people who have had similar experiences. As well intentioned and committed as policy makers may be, they often don’t understand that frame of decision making that can lead someone from point A to point B.

Gun violence is a symptom of a much deeper, chronic brokenness within the community. We have seen staggered increases in police budgets that are sapping resources that we could be using to help support healthier and inclusive schools, advancing our transit system and creating more subsidized childcare. When we focus on police intervention, it leaves less support for the preventive and intervention models that many within Black communities are calling for.”

— ANTHONY N. MORGAN, RACIAL JUSTICE LAWYER AND COMMUNITY ADVOCATE

“Black, Indigenous and people of colour are more likely to rent in Toronto, which makes them more vulnerable to housing price increases, rent increases and eviction. Racialized people are more vulnerable to the gaps in the system. But the policy process itself doesn’t address these issues. The average attendee of a community planning consultation is a white, male homeowner over 65. Due to their lived experience, affordable housing is not as much of a priority as it would be for a renter or someone who’s lower income. And the style of consultations often doesn’t allow for marginalized members in the community to give feedback on deep-seated issues.

In the next 20 years, the city should partner with community centres that are currently the ones doing the work and have connections and relationships with marginalized members of the community. Affordable housing needs to be the guiding star in these partnerships. And we need to define ‘affordable’ in a way that means it is affordable to marginalized communities. Rents should be geared to income, not tied to the market. The industry and urban planners should collaborate with tenant associations. They know intimately what it’s like to live in a situation where the housing system is not working. In an equitable market, we would have more community-owned housing that is separate from the privatized market.”

— CHERYLL CASE, URBAN PLANNER

“Toronto has the largest population of First Peoples in the country. There are 70,000 people right here. [The city has] about 20 Indigenous health and social services – including one clinic, Anishnawbe Health Toronto – and we’re lucky that the majority have Indigenous boards and governance. But that is not enough to serve 70,000 people, and when it comes to funding, we get left behind.

In health care, if you have to go to a service that doesn’t make sense to you, then you’re less likely to trust it. Because of high rates of anti-Indigenous racism and 500 years of family disruption, when Indigenous people do seek care and we’re very ill, we’re misdiagnosed as intoxicated. Many people try to hide or ‘pass,’ because that’s how we’ve survived in cities where only harm comes from being identified as Indigenous. And health information systems are worse for Indigenous people. We track some of the inequitable impacts of COVID for people who are Black and people of colour, but not for Indigenous people.

In order for Toronto to become more racially equitable in 20 years, settlers across all races need to recognize and respect Indigenous sovereignty.

And I cannot overstate how important it is to actually have Indigenous leadership at the table. For example, in response to COVID, the Well Living House helped open the Auduzhe Mino Nesewinong clinic because Indigenous people were not able to access culturally safe public health responses. We provide comprehensive supports, including education, outreach, testing, case management and contact tracing. We’re doing that with Native Men’s Residence, which is one of the only Indigenous-specific shelters in the city, and Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, an Indigenous midwifery program. Now, we’re doing it ourselves.”

— JANET SMYLIE, FAMILY PHYSICIAN, DIRECTOR OF WELL LIVING HEALTH, THE INDIGENOUS HEALTH RESEARCH UNIT AT ST. MICHAEL’S HOSPITAL, AND PROFESSOR AT UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO